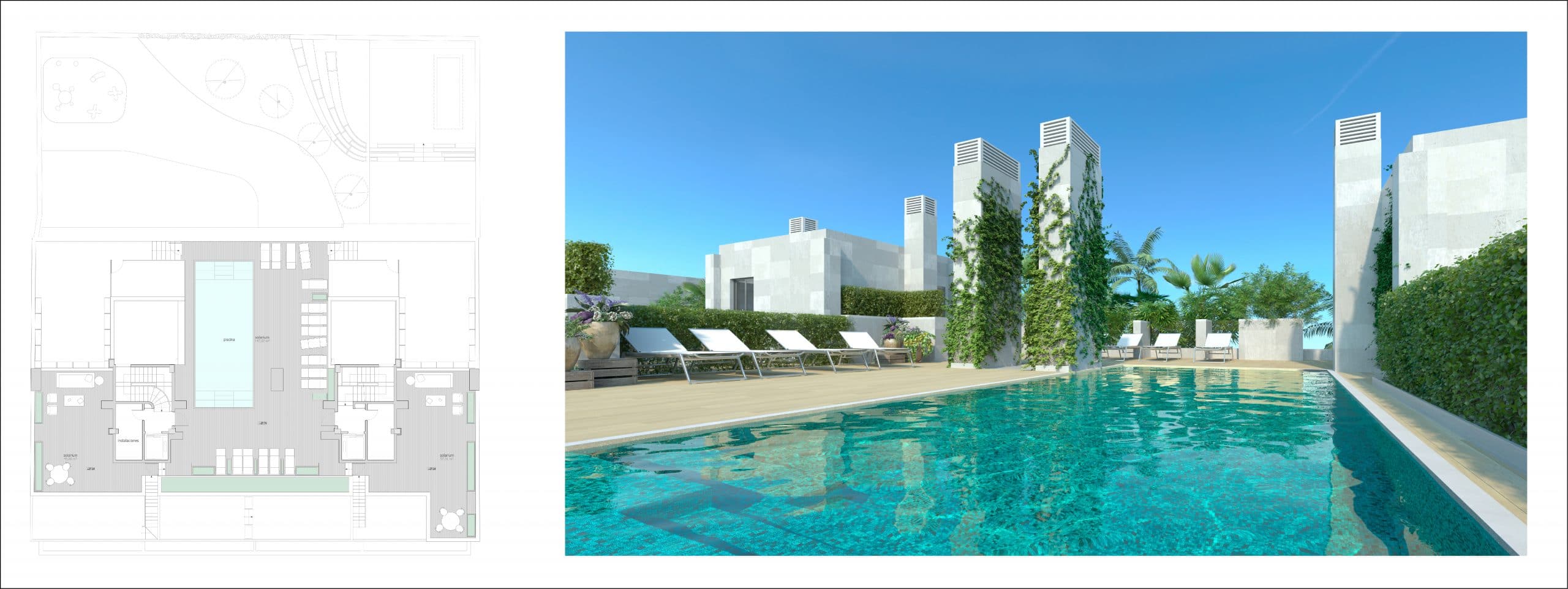

The use of images and 3D renderings to create architectural atmospheres has skyrocketed in the last few years. The huge technological advances on a graphics level and the access to information via collaborative platforms have led to a highly talented industry that often makes us question whether we’re seeing something real or not.

These images are today the main way to represent the most important ideas and concepts of a project on a visual level. They’re an essential resource so that clients, who aren’t normally architects and aren’t expected to understand a floorplan, can understand the keys of the project and get an approximate — not final — idea of the concept behind the type of architecture chosen.

Atmospheres in architecture

The concept of atmosphere has been approached from various philosophical currents and fields of knowledge. Every day, when we talk about the term atmosphere, we refer to a spatial feeling that is present in the space. In philosophy, the German author Hermann Schmitz, a founding father of research on the concept, explores the notion of atmospheres in a way disconnected from the methodological character and conceives it in a broader term as ‘different moods’ (Der Gefühlsraum, 1969). Paraphrasing Böhme (2012) and following the German philosopher’s contribution, an atmosphere can be pleasant, tense, elegant, melancholic, positive, charged, etc.

In architecture, the concept has also been studied from different approaches, although the Pritzker Prize architect Peter Zumthor is recognised for exploring the term of atmospheres in architecture.

According to Zumthor (2006), “when I enter a building, I see a space and I perceive an atmosphere and, in a fraction of a second, I have the feeling of what it is”. In this sense, the author adds a component of emotional sensitivity to the concept. A perception that is captured in the speed of light and which evokes a feeling that captivates us and influences our way of seeing things.

“For me, architectural reality can only be about whether a building moves me or not. What the hell moves me about this building? How can I project something like that? (…) How can things be projected with such presence, beautiful and natural things that move me again and again?”(Zumthor, 2009)

Atmospheres in architectural visualisation: definition

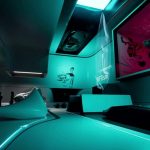

Atmospheres in architectural visualisation can therefore be defined as an aura of feelings that surrounds the images and that can trigger emotions in the receivers to influence decision-making. A subtle instrument of persuasion that gives off and can evoke memories — mostly positive — through the treatment of the image: colour, light, textures, shapes, composition, etc.

“The atmosphere speaks to an emotional sensitivity, a perception that works at an incredible speed and that humans use to survive. Not in all situations do we want to think for a long time about whether we like it or not, about whether or not we should get out of there quick. There’s something inside us that immediately tells us a lot of things; an immediate understanding, an immediate contact, an immediate rejection” P. Zumthor, 2006.

The difficulty of making an impact with images

Today, it’s difficult to be relevant and to move people within a hyperconnected world. Everything happens at breakneck speed and we’re bombarded with images everywhere. Multimedia apps and social media platforms such as Instagram, where quantity is more important than quality, make it difficult to find visual representations that are really worthwhile. Yes, we can see dozens of images in a matter of minutes, but we don’t pay even the slightest attention to them. Therefore, we need to (re)learn how to observe.

Juhani Pallasmaa talked about this phenomenon in his book The Eyes of the Skin (1996), in which he said that “the only sense that is fast enough to keep pace with the astounding increase of speed in the technological world is sight. But the world of the eye is causing us to live increasingly in a perpetual present, flattened by speed and simultaneity”

Therefore, and following what Zumthor stated, it is necessary to impregnate the images of an “atmosphere” that is capable of transporting a highly saturated receiver to an idyllic environment, where, through different visual techniques, they can experience emotions that make them remember what they’re visualising. What’s more, events that have an emotional content, either positive or negative, affect the process of coding, consolidating and evoking information. In other words, they foster memory (J. Nadia M. Psyrdellis, E. Ruetti, 2013).

Language in architectural visualisation

The creator doesn’t try to trick you or make you think of something that it isn’t actually is. A visualisation isn’t manipulation; it’s what the author interprets. Their experiences, their ideas and an overall picture of everything. It’s what they think is going to happen, for example, when the sun’s rays hit the façade. Or what the passer-by will feel when they walk among greenery.

Images produced by a 3D model through programs such as Lumion, Maya or SketchUp are as useful as a floorplan, a construction detail or a sketch. We must be very clear about what we can convey with each of them and when to use them. It’s not the same to persuade a client or a jury through a floorplan than to do so through a render full of emotions where they ‘can see’ (and feel) what it will be like to interact with and in the new project.

In no case will these forms of architectural visualisation fully reflect reality. They’re simply an approach to what the eye and the human psyche will see and feel when they are there.

About the author

Miguel Iniesta

Graduate in Architecture from the Polytechnic University of Cartagena. Since 2017, he has worked in the field of architectural visualisation, collaborating and learning from studios such as Agraph. Since 2019, he has been part of the ADORAS team, working on architectural visualisation and project design.

Graduate in Architecture from the Polytechnic University of Cartagena. Since 2017, he has worked in the field of architectural visualisation, collaborating and learning from studios such as Agraph. Since 2019, he has been part of the ADORAS team, working on architectural visualisation and project design.