The COVID crisis questioned our way of living and how it is conditioned by the architecture we live in.

After having been locked down for more than five months, many people realised that their home or their surroundings don’t fit in with their new needs. There have been a whole host of responses to this situation, including partial or total renovations, new consumption habits, changes of residence, etc.

In architecture, several fields of reflection and experimentation had already been explored before the pandemic. Examples include the curatorial line of the 17th International Architecture Exhibition in Venice proposed by Hashim Sarkis as a (visionary) question (How will we live together?) or the housing proposals of some of the most recent Pritzker Prize winners such as Alejandro Aravena or Lacaton & Vassal.

Specific responses from the profession to these new housing demands include models of collective living such as co-living and co-housing.

Background to co-living and co-housing

As we have been seeing in recent months, a crisis outside architecture has highlighted the shortages we’re suffering from in terms of housing. If we look back on recent history, we’ll see how this has been repeated before and how the profession has given different answers.

Particularly sensitive to these crises are urban environments, which is where the responses come from. This was the case with the mass exodus to cities during the Industrial Revolution which gave rise, for example, to the first Soviet communal buildings. These were the inspiration for Le Corbusier in his reflection on urban design which, after the Second World War, materialised in collective housing projects such as the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, where housing is integrated with basic services.

Later on, we can look at the housing experiments developed in Denmark. In 1967, Bodil Graae questioned the structure of the traditional family unit by writing a newspaper article titled “Children Should Have One Hundred Parents”. The idea of replacing the family unit with collective groups had been reflected earlier that decade by Aldous Huxley in his utopian society novel “Island”. These thoughts saw their answer in the layout of the Saettedammen project in Denmark developed in the early 1970s. This was a community of twenty-seven houses in which families of all ages live together, with a large communal area and a community house for all residents.

Co-living in Spain

The Spanish case is somewhat unique as industrialisation was relatively recent, as was the mass exodus to cities. What’s more, it largely took place during a dictatorship that focused life on rural communities. In fact, the relationships between public and private life imagined by the different models of co-living are (were) the usual ones in rural environments.

The year 2009 was key to the recovery of these ideas with the Nobel Prize in Economics being awarded to Elinor Ostrom for “her analysis of economic governance”, which she continued to develop in works that studied the elements or variables that influence the possibility of self-management of communities in relation to the development of sustainable socio-ecological relationships. With COVID, we’ve been able to see that we’re empathic with a social entity.

What is co-living and co-housing?

Both co-living and co-housing are a way of living in which the user wants to relate to their neighbours and share common spaces and services. However, there are substantial differences between with regard to the management and ownership model, as well as the user profile.

Characteristics of co-living

On the one hand, we have the co-living model, geared towards a young childless user who can work from home. In this model, there’s one owner who rents out properties to users and manages the communal services. The user is looking for management of their time rather than management of their living space, i.e., they want to have everything at hand. Tenants usually stay for a short time and the properties tend to be small because the services are shared. As user profiles are very similar, the concept fosters a sense of networking but in domestic life.

If we take into account the preferences of users when choosing a co-living space, amenities are essential. A co-working space is the number one priority, followed by a gym. The reception service is also very important, to such an extent that sometimes it’s almost like a personal assistant that manages everything. The other important point is the environment, with Internet-based shared management of energy to minimise consumption.

Characteristics of co-housing

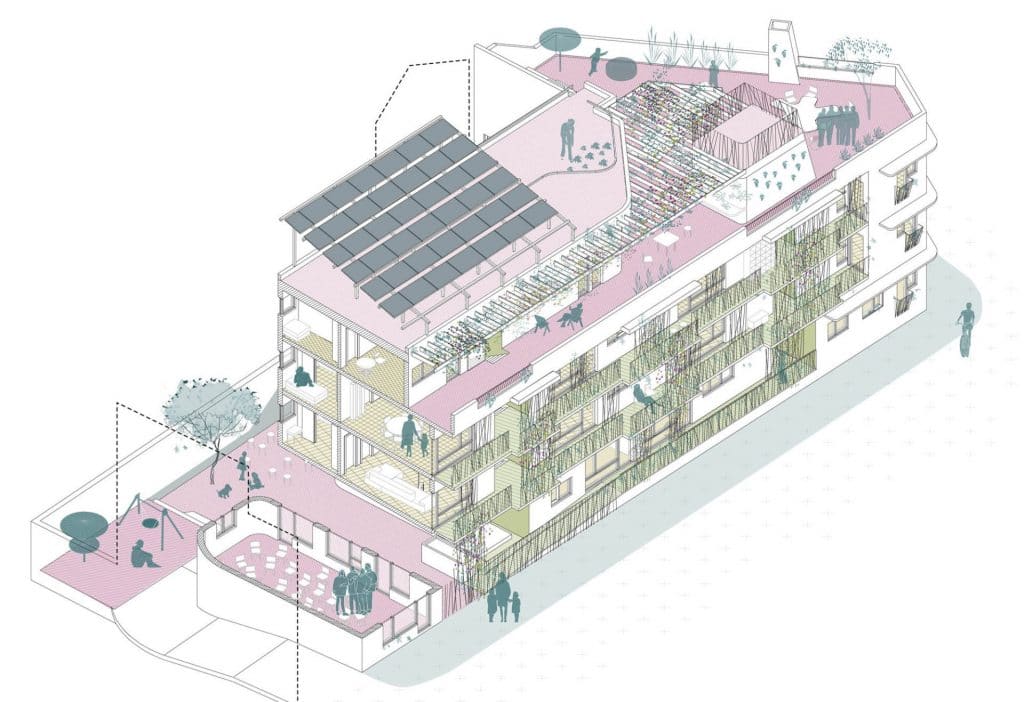

In co-housing, the ownership model is usually cooperative and members have the right of use. These members develop the project from scratch (supported by professionals), planning what the homes and common spaces will be like and, once built, managing the services and facilities. The goal is to live in a collaborative community.

For co-housing residents, preferences tend to be geared more towards outdoor spaces such as gardens, but also shared kitchens, playrooms, nurseries, workshops, and so on. However, each community decides its own needs. In terms of eco-efficiency, passive and local material solutions are often provided.

Post-COVID housing model

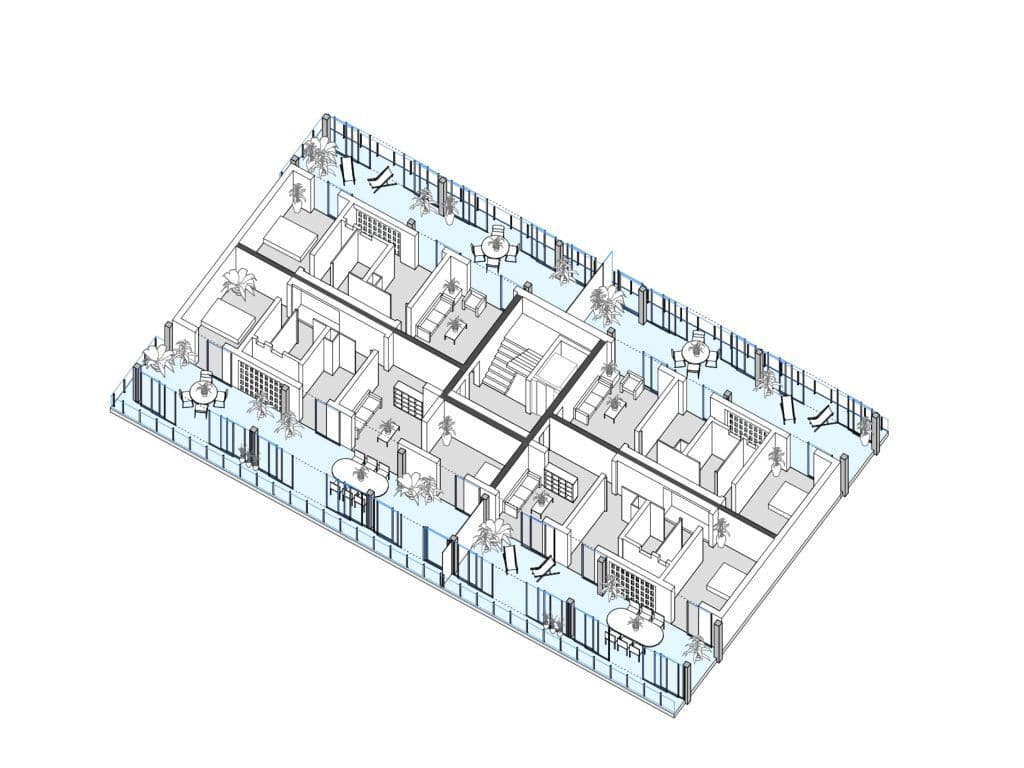

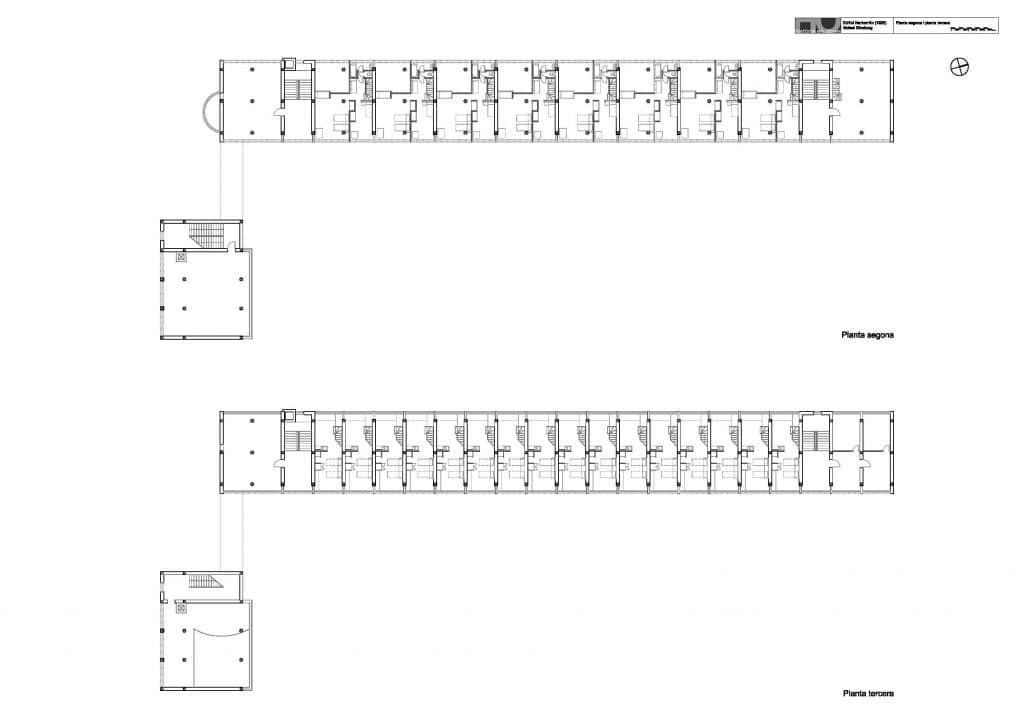

At ADORAS atelier architecture we’ve studied the co-living model to expand the range of users, generating a type of resilient housing adaptable to each user and their needs. These are modular properties, which can be joined together and with movable partitions that adapt the spaces.

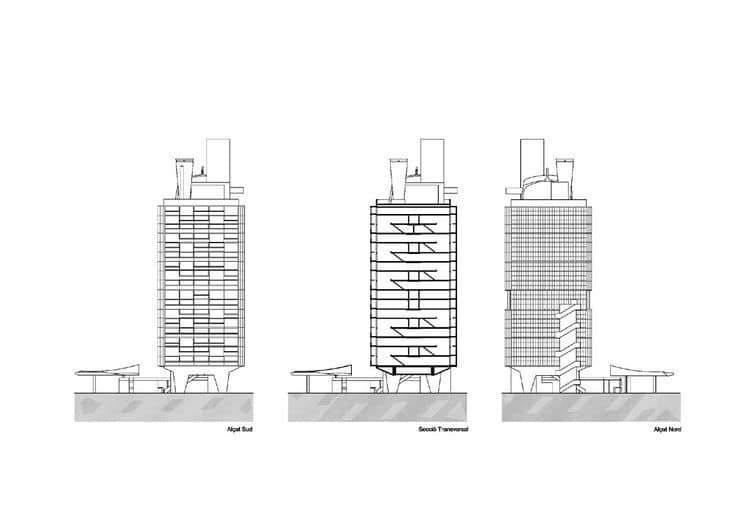

What’s more, we’ve developed high-rise buildings with these modular properties, featuring communal safe spaces on different floors, a way to leave the house without being outside as such.

At STAY by Kronos we’ve turned all these ideas into a co-living concept in which users live in a ‘small city’ where they share a series of amenities and can use an app to manage all these community spaces and keep an eye on consumption levels.

About the author

Luís Ceñal

Graduate in Architecture from the University of Architecture of Alcalá de Henares and currently studying an executive PDD at IESE. He developed professionally as an architect in London at studios such as Belsize Architects (RIBA Award winners) and BPTW, where he worked as a project manager for residential complexes of more than 350 homes. At ADORAS he has worked as a department director since 2019, where he contributes his international experience with Northern European design and processes.

Graduate in Architecture from the University of Architecture of Alcalá de Henares and currently studying an executive PDD at IESE. He developed professionally as an architect in London at studios such as Belsize Architects (RIBA Award winners) and BPTW, where he worked as a project manager for residential complexes of more than 350 homes. At ADORAS he has worked as a department director since 2019, where he contributes his international experience with Northern European design and processes.